One Hand Clapping – August 2004

— William Michaelian

Note: Each month of One Hand Clapping has been assigned its own page. Links are provided here, and again at the bottom of each journal page. To go to the beginning of Volume 2, click here.

March 2003 April 2003 May 2003 June 2003 July 2003 August 2003 September 2003

October 2003 November 2003 December 2003 January 2004 February 2004 March 2004

April 2004 May 2004 June 2004 July 2004 August 2004 September 2004

October 2004 November 2004 December 2004 January 2005 February 2005 March 2005

August 1, 2004 — “O Happy Day.” Early this morning on “The Gospel Express,” a show hosted each Sunday by Derwin Boyd on KBOO radio in Portland, I had the good fortune to hear this classic sung by the Edwin Hawkins Singers. I love all kinds of music, from Beethoven to the Beatles to Bluegrass to the Blues, and I can honestly say that I am just as thrilled to hear “O Happy Day” as I am to hear “Ode to Joy” from Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony — and I am nearly paralyzed by the latter. I’m paralyzed by all good music. I was paralyzed yesterday morning when I heard, again on KBOO, Marty Robbins singing “Unchained Melody.” I was paralyzed when I heard Tammy Wynette sing “Yesterday,” by Paul McCartney. And I am paralyzed when I hear Johnny Cash sing “Ghost Riders in the Sky,” and when I hear Louis Armstrong and Ella Fitzgerald sing Gershwin’s “Summertime.” In fact, with so much good music in the world, it’s a wonder I can get around at all. Good old Derwin Boyd. Week in and week out, he says, “Lord, have mercy. We gonna move, groove, and be smooth, right on down the line.” He also says, “This rotation is for your one and only appreciation.” In other words, he wouldn’t get very far working for Corporate Rock Radio, or Corporate Oldies, or Corporate Smooth Jazz, or Corporate Country. Indeed, in that constrained environment, he would suffocate within two hours. He’s far better off as a volunteer DJ at KBOO, a small, independent, member-owned advertisement-free radio station. And I am better off, and stand a far better chance of hanging onto what remains of my sanity, listening to KBOO, instead of the constant barrage of advertising and lightweight, insincere DJ babble on the other stations. Lord, have mercy. How we gonna move, groove, and be smooth if someone’s yelling at us all the time, and telling us where to buy our pizza, diamonds, cars, and gutters?

August 2, 2004 — A dewy, poetic, rose-scented romance such as Mademoiselle de Maupin deserves to be read in the evening by candlelight, and not at five-thirty in the morning as, for the most part, I have been doing. But the other evening I did manage to read a chapter outside, while sitting in a tattered lawn chair beside our tomato plants. It’s not that I lack culture. I’m aware of the way things can and should be done. I’m also aware of the way things sometimes have to be done, if, indeed, they are going to be done at all. Still, I can’t help recognizing that the characters in Théophile Gautier’s book would turn their noses up at me, unless, perhaps, I was employed as their gardener or stableman, in which case they would deem me harmless and see to it that I had a decent pair of boots. Were Rosette and D’Albert to learn I had been listening outside the window of their love nest, they would smile at my lumpy peasant curiosity and then continue about their business. After all, everyone has their job to do. Some of us are born to indulge ourselves in the harrowing pursuit of love when love is already within our grasp, while others are born to keep their masters’ horses and automobiles at the ready, should they feel the need for a late-night hamburger or a moonlight walk through the countryside. Such is life, I guess — or at least such will life be until I finish the book. After that, depending on what I pick up next, life will be something entirely different — a train ride through Siberia running away from or toward my doom, or fifty years spent talking about sports and the weather in a small town barbershop, when all I ever really wanted was to be a park ranger. And such is life, that books make it possible to inhabit more than one existence simultaneously, and that the happenings in really good books so often intersect, run parallel, or collide with our own.

August 3, 2004 — D’Albert’s latest confession to Silvio, the old friend to whom he addresses the long, flowery letters that so far have made up almost the entire narration of Mademoiselle de Maupin, is that he is in love with a man. The confession itself filled several pages, though it might have been done in a paragraph. Indeed, I saw it coming from the first few sentences, and thought to myself, “Come on, just say it and move on.” Meanwhile, I suspect that this, too, will be just a passing phase in D’Albert’s self-absorbed existence, as a little over half the book remains. A few chapters hence, I wouldn’t be surprised if he is in love with a horse. For D’Albert, who is sensitive to the extreme, this is entirely possible. That’s why I will stick with the book. I want to find out what happens to the horse.

August 4, 2004 — Assuming I survive the French horse affair, the next thing I plan to read is John Steinbeck’s Cannery Row. I borrowed my mother’s copy yesterday. It’s resting just beyond my keyboard atop Faulkner’s The Reivers, about an inch and a quarter to the right of my recently acquired volume of Shakespeare, which at the moment is holding up Gautier (he’s very weak and needs help, poor guy) and my glasses. And I am embarrassed to say that my table is covered with a thick layer of dust once again. Having had our windows open for many hours a day for several weeks running, a fair portion of the Willamette Valley has settled over my work area. It’s The Grapes of Wrath all over again. I should clean it up, but in honor of Steinbeck and agriculture I think I’ll wait until I’ve read Cannery Row. Anyway, there’s a lot less dust in Monterey, California, where the book is set, and no shortage of fog, so I don’t expect things to get too much worse over the next week or two. Besides, what does it matter? So everything’s dusty. Things are supposed to be dusty this time of year. Strangely enough, this reminds me of something a friend of mine said to me many years ago after I’d used the bathroom in his apartment in Fresno and told him in no uncertain terms that he had the dirtiest toilet I had ever seen, and that he should be ashamed to have let it get to that stage. His answer? “It’s a toilet. Toilets are supposed to stink.” We had a good laugh over that one. The next time I was at his apartment, though, his toilet was spotlessly clean, and it remained so. About a year later, his mother arrived from Istanbul and moved in with him, and immediately took over all household duties. Not only did she keep the bathroom clean, there were handmade doilies everywhere, and Old Country quilts stuffed with wool. Now they live in L.A., and I hear through the grapevine that my friend is married and the father of eighty-two children, each with his or her own toilet, which their grandmother keeps clean. This is typical of grapevine information, but it’s better than no information at all. I also hear they are running a doily factory, and that this has attracted the attention of none other than the great Tom Ridge, head of Homeland Security. Like Middle Eastern cooking clubs, doily factories are known to be hotbeds of terrorism. Thank goodness Mr. Ridge is on the job — especially since he looks like a cross between Dick Tracy and Alley Oop, and issues terrorist alerts based on four-year-old information. With Tom on our side, how can we go wrong?

August 5, 2004 — Well, well. Théodore is not Théodore after all. He is a she. And she is none other than Madelaine de Maupin, who has disguised herself as a man in order to spend time with men when they are not around women and thereby learn what they are really like before allowing herself to be loved by one. That’s pretty tricky, and Madelaine is pretty gutsy to leave home, and on her first night out sit in a wayside inn and have drinks with the boys on a tempest laden night. Luckily for her, everyone is too drunk to notice her long eyelashes, delicate features, and less than rugged voice, and is taken in by her strategic ensemble. Later, because the inn is crowded, she even has to share a bed with one of her drinking buddies. While he sleeps the sleep of the dead, she lies wide awake beside him, wondering what would happen if he woke up and discovered the truth — wondering, in fact, what would happen if she woke him up and explained it to him herself. But she doesn’t. She survives the night without sleeping a wink, and arises with her virtue intact to face the dawn, then goes her own way. So. Now we’re getting somewhere. It’s only a matter of time until D’Albert realizes the truth, which to his trembling poetic delight he has already begun to suspect, perceptive soul that he is. . . . Meanwhile, back here on earth, I read this morning that Guy de Maupassant was born 154 years ago on August 5, 1850. When he first read Mademoiselle de Maupin, I can imagine him thinking, “What the heck? This Gautier is nuts. I don’t care what Balzac and Hugo said.” Indeed, according to the book’s introduction, Honoré de Balzac and Victor Hugo hailed Gautier’s book as a masterpiece when it came out in 1835. As it turns out, most of the book was written when the author was twenty-three. When I was twenty-three, I was a father and had already been married four years. Our daughter was hailed as a masterpiece by everyone in the family, and since then has received nothing but rave reviews. She hasn’t been translated into dozens of languages, but she does know a lot of Spanish, and was able to haggle with taxi drivers and street vendors when she was in Ecuador several years ago. But I have no desire to diminish Gautier’s efforts. He did his best.

August 6, 2004 — A while ago a nice shower blew through, settling the dust, perfuming the air, and drenching our south-facing window sills. I toweled them dry and reluctantly closed the windows, but have since opened them again part way, as the rain has stopped and I hate to miss out on the fresh breeze. The front door is also open. This is unusual weather for early August, but certainly not unheard of. Rain-lover and heat-hater that I am, I see it as a day stolen from the jaws of summer. But I fully expect another blast of heat in short order. After all, it is August. There are more ninety-degree days yet to come, as well as more sudden adjustments to be made by that ridiculous lumpy thing known as the human body. By gum, at this very moment, I can almost feel myself retaining water in preparation for the next heat wave. Within two days I will have gained five pounds, and will be able to hear myself slosh as I chug around the house in my underwear, looking like a grotesque, aged stump. In fact, I have long thought that the best way to scare off the neighbors is to make shirtless appearances on the sidewalk with a can of beer in hand. Then again, my shaggy appearance already has them scared — though when I think about it, puzzled would probably be a better word. Anyway. This is all nonsense. No one really notices, and no one cares. The neighbors race by in their cars with their cell phones glued to their ears, in a pointless frenzy and worried to death. This is at seven or eight in the morning, not thirty seconds out the door. I understand how they feel, and am fully aware of the financial and emotional concerns that drive them. But I also know that an unfortunate amount of what we suffer in so-called modern life is self-induced, in that we don’t grant ourselves a quiet moment now and then in which to think things through. We insist on constant activity, entertainment, and noise, when what we really need is to take a walk or sit quietly for an hour and do absolutely nothing at all. Most unfortunate, I believe, is how we are conditioned by television, and to what extent our speech and mannerisms have come to reflect the poisonous nonsense that is served up twenty-four hours a day. Who needs it? Coincidentally, I saw a great bumper sticker yesterday that said, “You wouldn’t dump garbage in your living room, so why let TV do it?” How true, except a lot of people do dump garbage in their living rooms — at least I assume they do, because they also dump their garbage in the street, in the form of fast food wrappers, cans, bottles, and so on. What a filthy, self-absorbed way to live. I will go so far as to say that people who litter are, in their present mental state, incapable of appreciating nature. As it is, being out of touch with nature is one of our most serious problems. The same thing that happens to our penned-up animals happens to us. We gradually lose our ability to observe and respond. We need a television weather person to tell us what should be obvious by going outside and sniffing the wind. We are oblivious to the changes in our body and what they mean, and to the timeless activities of plants, insects, and birds, which can tell us all we need to know. We eat improperly, don’t exercise, and consequently go to pieces. In this condition, we form our opinions and make our decisions. We think we are intelligent, but we couldn’t grow a potato or milk a cow if our life depended on it. And who knows? Maybe someday it will.

August 7, 2004 — The big news, the exciting news, is that I made pancakes two times this week, thus ending our pre-dawn scrambled egg marathon. They were heavenly. And making them is an emotional experience, because it takes me back to when my father made pancakes for me when I was seventeen and working at the packing house. As I watch them cook, spatula in hand, it is as if he is standing there beside me. Aren’t those ready to turn? I was just going to turn them. It looks like they’re ready. I’m turning them now. There. See? Perfect. How many would you like? Four? I could eat twice that many. Eight it is, then. Sit down. There’s the paper. Don’t you want some coffee? No. I’m going now. Going? What’s your hurry? I can’t stay. You know that. No. Wait. Don’t leave. I’m going. . . . Oh, God damn it all. . . . an eruption of wings, footsteps in the dust, a falling star, light shining on a drop of dew. Good-bye, good-bye, good-bye for now. And good morning to you, dear son. Here are your pancakes. Eat them and rejoice. Eat them, and be aware of the spirit in this room.

. . . Ah, grief. My old friend. You have found me once again. I see you are well. Sit with me, then, and we’ll talk awhile.

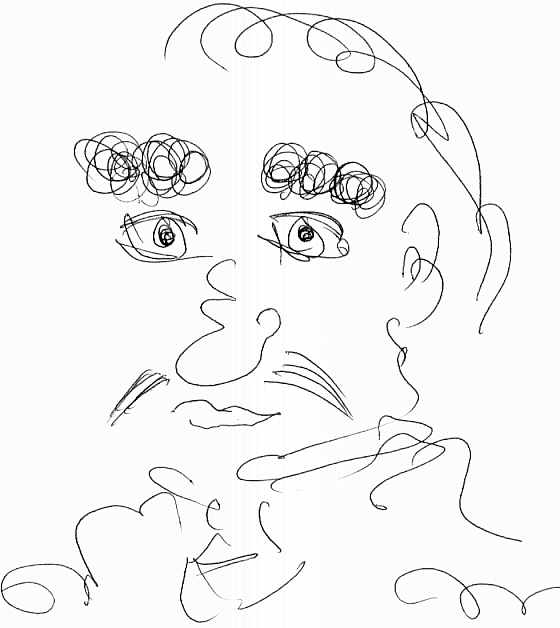

August 8, 2004 — Miss de Maupin was a singular girl, at least as far as D’Albert was concerned. To others, she was a singular young man with superior command of rapier and steed alike, and always busy fighting duels. What a sensitive lass! what a daring lad! — so very near a god was she, and forever young, for we know not what became of her after the one and only night she granted D’Albert, whose heightened dreams of love and beauty were finally realized. But what a nightmare for D’Albert’s beautiful mistress, Rosette, who loved Madelaine as a man. One can only hope she and D’Albert were able to find solace in each other, even if their love was of the earthbound variety. I wonder. D’Albert was a poet. It is unlikely that he went on to enjoy a career in banking or real estate. And it is equally difficult to picture Rosette as a mother with dish pan hands, hurrying to her next P.T.A. meeting. O Life! Sometimes you are just too much! And you, Théophile Gautier, with your honey-dipped pen! What are we to make of you? Shall we set about finding your complete biography written by some sensible scholar, or shall we allow you to remain hidden in the literary mists of time? Shall we dissect your corpse with detached precision, or give thanks for your rose-scented phrases? Even now, we can hear you laughing. We can hear you say Do as you like, for it doesn’t matter, and can never matter in the way any foolish, practical person thinks it matters. We can examine each and every stone that you encountered on your path through life, but we will still be confounded by the rubble. Therefore it is our decision at this time to offer you our heartfelt gratitude, and to move on to Steinbeck’s Cannery Row, set in a new century that has since itself miraculously grown old. As for the current century, childishly referred to as the twenty-first, I fear it has already grown old before its time, so tragically debauched it is, so shallow, ignorant, narrow-minded, and self-centered, so without grace and style, as if its hundred years were an illiterate doodle on a CEO’s list of things to do. By gum, we need to do something about this. We are not even a decade into the century, and already it reeks. Where is our spirit? Where is our flair? Where is our sense of humor? Why are we offended at every turn, and in such a hurry to press legal action? Are we really that insecure? Is it really our nature to act as wolves, jackals, sheep, and hyenas?

August 9, 2004 — I’m off to a sluggish start this morning, mostly because the heat has returned. It was ninety-five yesterday, and today is going to be hotter. Life on the Pacific roller coaster continues. We bought a big watermelon Saturday morning, a hefty twenty-nine-pounder; this will serve as our air conditioner. We also have plenty of ripe home-grown tomatoes, and plenty of salt, so we should survive. And really, there isn’t much more to ask for. We will either figure out the rest later or we won’t, and the disappointing actions of family members and loved ones will either be explained or they won’t, and we will either sustain lasting scars or achieve new levels of understanding or both. That’s why it is just as reasonable to put our faith in watermelons and tomatoes as anything else, and probably better. At least watermelons and tomatoes are real, and are honest, dignified representatives of this vast, wondrous universe. And having said this, it should also be noted that I have just closed our windows to ward off the pollution drifting eastward from the freeway. What a shame we have taken simple elements and mixed them up in such deadly fashion. One would think we’d be smarter than that, especially since we brag about our brain power so much, but we’re not. Watermelons are smarter. Watermelons don’t pollute. They don’t cut people off in traffic and yell obscenities, or line up with other watermelons and try to kill other kinds of melons on the other side of the world, the stripes versus the greens, the longs versus the rounds. Watermelons don’t kill in the name of religion. They give life, and in the process lose their own. It would be nice to be a watermelon, and to bring joy on a hot summer day. Then again, they say we are what we eat, so maybe there is hope for me yet.

August 10, 2004 — In honor of an untold number of poetically aligned and misunderstood events, I lit a cigar a few moments ago. This is something I haven’t done in the last two, or maybe even three years. I have never smoked regularly, and smoking has never been an established habit, but I have loved the activity since I lit my first nickel cigar when I was in high school, and even long before. My father smoked cigars for years, as did his legendary Uncle Archie, who not only smoked them, but chewed them violently as he educated us on diverse subjects in his booming voice. In his cigar-smoking prime, which went on for decades, Archie smoked about ten or twelve cigars a day. Archie was also a first-rate poet and painter. It is quite understandable, then, that I would think of these great men now, as I sit here in an agreeable cloud of smoke and set about my day’s work. It is more than agreeable — complemented by my first cup of coffee, it is a moment straight from heaven. As a kid, Dad would smoke anything he could find, including discarded butts on the roadside. And I have mentioned before how in his eager quest to smoke he even sampled dry horse manure, which he found a bit harsh, and which probably kept him from sampling other varieties of manure. Ah, well. Those were the good old days — days I am reliving to some extent since having begun Steinbeck’s delightful and easy-going Cannery Row. That this could be, even though I wasn’t around in the 1930s, I regard as a profound, yet natural bit of good fortune. Had it not been for my parents and an amazing cast of storytelling relatives, I fear this would not be the case. Certainly, I would not be who I am, and there is an excellent chance I wouldn’t be doing what I am doing. I suppose this is both obvious and meaningless, or at least the thought is so common that it seems meaningless. Be that as it may, this is for me a tremendously happy moment, especially since a lump of ash just landed in my lap and on the edge of my keyboard. Though it probably won’t work out that way, I feel as if I will remember this moment forever. One thing I know: it’s mine, and no one can take it away from me. But I’m not a selfish person. As far as it is within my power, I give it to you to enjoy, with the sincere wish that it awakens similar memories. Such is life on this fine August morning.

August 11, 2004 — As I had feared, this has turned into a week to survive, as temperatures continue in the middle and upper nineties. Each day the air is a little dirtier and harder to breathe, and each night the house is hotter and sleep is harder to come by. It isn’t bad inside until about four in the afternoon. The indoor heat is at its nastiest, and the air is most stale, at about seven in the evening. Then the heat begins to break and we can open the windows again. Last night at nine o’clock, it was about eighty-five in the hottest part of the house, which also happens to be our bedroom. We use fans to bring in the cool night air, but the walls and attic are so hot that it takes all night to cool the house. Then we start all over again. As a result, I stagger around with dark circles and bags under my eyes during the day, barely functioning. And, to add insult to injury, our long dry spring and current hot weather have caused legions of ants to swarm all over the house, and to appear inside where you least expect them. Lately, for instance, there have been ants in the shower, coming from the area where the pipe that feeds the nozzle goes into the wall. This means, I presume, that the wall is full of ants. A few days ago, when it cooled off and rained, there was no ant activity. There are also a lot of yellow jackets this year, and tons of little brown spiders, which will later be big brown spiders. We are already walking into their webs. With any luck, the webs will soon be thick enough to give shade and cool the place down.

August 12, 2004 — Tomorrow Portland will have to endure simultaneous campaign visits by the two eminently cool dudes running for president, George Members Only Bush and John Come One Come All Kerry. As so often happens, Bush will be speaking behind closed doors to a pre-approved crowd of loyal supporters, while Kerry’s rally is open to the public — an evil ruse if there ever was one. Hopefully the good voters of Oregon will see through Kerry’s bogus tactics and pledge allegiance to our current emperor, so he can continue his fight against tourism — I mean terrorism. What a leader. What a man. What a hero. Hail to the Commander in Thief of the Harmed Forces of the United Fakes of America. Oops. Sorry, mister. I didn’t mean to bump into you. Hey! Where’s my wallet?

August 13, 2004 — Thank goodness George Did It All By The Sweat Of My Brow Bush is arriving in Oregon just as figures were released showing the state is still a job seeker’s, grocery buyer’s nightmare. From an undisclosed, heavily guarded, by invitation or ticket only location, his compassion will rise up and act as a balm for the weary masses. “He’s one of us,” will be the general refrain. “He’s our friend.” Then Georgie Porgie will fly away, flappity flap flap, leaving the people to sink or swim, and their kids to rot in under-funded, overcrowded schools, where they will do without art and music and be ideal recruitment targets. Thanks, old buddy. It was nice of you to drop by. Be sure to let us know if you need anything. We don’t have much, but what we have is yours, or soon will be. Now, if you will excuse me, I have some work to do. I have to squeeze some blood out of a genetically altered turnip.

August 14, 2004 — Before moving on to genuinely interesting and important things, i.e., my life, it’s worth noting that an enthusiastic crowd of 50,000 was on hand for John Kerry’s outdoor public rally yesterday in Portland, while George W. Bush spoke before 2,300 ardent, pre-screened supporters. And there we will leave the matter, because it speaks plainly enough for itself, and especially because yesterday evening we gathered at my mother’s house and cranked up a batch of peach ice cream. Now, that’s important — as is the fact that we all took turns turning the crank in the ninety-degree heat, thereby earning the ice cream the good old-fashioned way. And what ice cream it was, and what wonderful summertime memories it awakened. When I was a little whelp, we used to make ice cream at the drop of a hat. When relatives dropped by, we made ice cream. When friends dropped by, we made ice cream. When someone drove slowly past the house, we made ice cream. Our old White Mountain freezer withstood an amazing amount of use. It could frequently be found full of water in the shade — necessary to make the wood swell and thus keep it a viable unit. But it did finally disintegrate. For a short time we had an electric freezer. It worked, but nobody liked it, because we knew we were cheating, and so we got another White Mountain. And speaking of home-made ice cream, there is a scene fairly early on in my novel, A Listening Thing, that involves a White Mountain freezer. It’s funny how these things work their way into pieces of writing. Obviously, when I included the ice cream freezer in the novel, I was writing about the one we used during the Sixties. Some might call this “writing what you know.” I call it inspiration. While I do know a lot about making ice cream, it is the spirit of doing so that moves me to write about it. It is the brain cells bathed in sweet memory. It is the joy derived from the work, the process, and the result. Ice cream has tremendous meaning. I have even written two stories with the title “Ice Cream” — one back in 1997, the other in 2002. The stories were about much more than ice cream, of course, but ice cream was still an important character in each. In fact, I can imagine writing a novel and calling it Ice Cream. Who could resist a book with such an appealing title? Probably the same people who can resist everything else I write, but that’s beside the point.

August 15, 2004 — Late yesterday morning, I took a leisurely drive through the countryside in our daughter’s 1991 Toyota Corolla. She bought a new-used car recently, but we decided to keep her old one, at least for the time being, because our youngest son, the iris farm hand, might find it useful one of these days. The car has 180,000 miles on it and it runs and shifts remarkably well. One thing it doesn’t have is very much paint, though it’s still possible to tell it was red at one time. Three or four days ago, Lev, our son who switches cars often for the sheer pleasure of it, had a mechanic-friend of his install a new serpentine belt. After the job was done, he instructed me to drive the car thirty miles or so, and said that he would then take it back and have the belt double-checked and tightened. And so I did as I was told, sticking to the country roads, taking my time with the window down — the car has no air conditioning anyway — and enjoying the standard transmission. I even lit another cigar, so that makes two cigars smoked this week. At this rate, I’ll become a real chain-smoker — except that my spare cash usually goes for used books, not cigars. Which reminds me — last week I invested another seven dollars in books. I was lucky enough to find the sixteenth printing of the fourth edition of H.L. Mencken’s The American Language, as well as a book containing two novels by Anthony Trollope, whom I’ve never read, and a hefty anthology of stories, poetry, essays, drama, and novels called A Quarto of Modern Literature. I like that — a quarto. Pardon me, but have you seen my quarto lying anywhere about? Damn and blast — I do believe I’ve lost it. I should have asked the crusty fellow I saw walking along the edge of a hops field, but he seemed to be enjoying his privacy so much that I couldn’t bring myself to stop. I was happy to see that the hops have reached the top of their massive trellises, and have begun to fan out over the wires. Early in the season, the empty framework always reminds me of streetcar cables. I saw a patch of cucumbers in which there was a small stack of bee hives, alfalfa fields, corn fields, and flowers being grown for seed. I saw the infinitely wise and patient Mother Earth in all her summertime glory. “Hello, dear,” I said. “You’re looking rather well.” The woman working at the Friends of the Salem Public Library bookstore asked me what I thought of Trollope, and wondered whether the name was pronounced Trol-lope, or Trollopé, or simply Trollop. I said I didn’t know, because I had yet to read Trollope, and didn’t know how the name was pronounced. She said she had picked up several of Trollope’s novels, but had yet to read any of them. I said, “Oh?” And she said, “Seven dollars.” The summer sky was hazy and magnificent, and the cloud-remnants of a thunderstorm that had briefly spattered the dust earlier in the morning were drifting eastward. Trollope worked for the Post Office for thirty years, and I think I read somewhere that he invented the street-side letter boxes that are used in England. But I could be dreaming. In fact, I know I am, but this changes nothing at all. Trollope did what Trollope did, for Trollope was Trollope, and could do only what Trollope could do. Scattered about us is an endless array of inventions that we take for granted, for we have forgotten the inventors suffering in their workshops — not because no one thought the inventions would work, but because the lighting was bad and their spouses wanted money for food. Ridiculous. Trollope wasn’t worried about such things. He wrote novels and worked for the Post Office. He saw a need and filled it, as they say at business seminars. It’s the same with me, except that I don’t fill the need. Rather, I create the need, and leave others to fill it. And if a statement like that makes sense, I have accomplished what I set out to do. If it doesn’t make sense, I have succeeded beyond my wildest dreams. Oh, where is that quarto of mine?

August 16, 2004 — The absence of departed family members is acutely felt on summer Sunday evenings, when food is on the table and talk is at its loudest, and outside the dusky shadows begin to fall. They are gone, gone, gone, and we are here, here, here. As our plates fill with the blood of fresh tomatoes, onions, and watermelons, laughter is both a sacred calling and a lunatic’s lament. We have a wonderful time, for anything less would be a disgrace. We are grateful for our memories, but we are also angry, because we share a feeling of outrage that springs from a history of family trials — massacres, emigration, poverty, fathers plucked from life early in their prime, long hours of physically exhausting work, children sent out to earn a living in the street, and success, a kind of trial all its own. We have won and we have lost, and in our losing we have gained, and in our winning we have been humbled. We are a gambling family, quite accustomed to betting it all. The stakes are high, the senses alert. Quite often, we do not know whether we have won or lost. But we feel like winners, even when we know we have lost. Summer Sunday evenings are like standing before a painting of our childhood, in which bolts of lightning pierce the canvas. They are a lonely shepherd watching his sheep from a high rock. The sound of his flute echoes the unspoken silence that informs and guides our conversation.

August 17, 2004 — From childhood, we are trained to believe that every problem has a solution, and that thinking otherwise is a sign of weakness. But is it really? While it’s safe to say most problems do have solutions, I think it’s healthy to admit that there might be an occasional one that is unsolvable or beyond our grasp. Some problems last for years and years, or even an entire lifetime. Take poverty as an example. A poor person can work his fingers to the bone and worry his nights away, and do everything within his power to alleviate his family’s pain and suffering, and yet never manage to bring it to an end. A problem of this magnitude can undermine his physical and mental health, make him see people and things in an unfairly negative light, and lead him to believe all sorts of terrible things about himself. In this condition, he doesn’t stand a chance. He is literally consumed by his problem. And yet if he is a man of conscience, and because of his childhood training, he blames himself and keeps right on banging his head against the wall. Surrounded by material wealth, he asks himself why he isn’t smart enough to figure out what it takes to get ahead in the world. The question is, what would this same person think if everyone were poor, and it was clear that the situation wasn’t about to change? Would poverty still be a problem? Would being poor even be recognized as such, or are poverty and wealth relative determinations? Isn’t it possible that if everyone were poor, they might not only think they are rich, but be rich? To put it another way, if you can’t win in a particular situation, it doesn’t necessarily mean that you lose. It just means you can’t win. What happens in a person’s mind when he acknowledges this possibility? What happens to the problem that has been torturing him for years? Does a problem remain a problem if it meets no resistance?

August 18, 2004 — I am especially pleased to be here writing today, because when the alarm went off at four-twenty this morning, I was dreaming that my death was at hand. I forget how the dream started, but toward the end I was taking clothes out of a dryer that was outside in a covered patio. As I was folding the clothes, two or three strangers were milling about, and one of them approached to see what I was doing. About that time, I realized some of the heavier socks were still damp, so I put them back in the dryer and turned the machine on again. This seemed to satisfy the stranger, who was an older Mexican woman. Then the strangers disappeared and I was alone. This is when I realized my time was almost up. It didn’t bother me at first. The only thing I was concerned about was getting my work done. As my rendezvous with fate approached, however, I began to feel tremendously sad. I said to myself, “Well, soon it will be over, and what I leave undone will remain undone.” I hated terribly the thought of being found by the family, and of them having to do something with my remains. It was a poignant moment. I can even remember the word poignant passing through my mind, and then feeling momentarily amused, because there also seemed to be an aspect of performance involved. But the amusement quickly passed. I was dying. I knew I was dying, and I knew I didn’t want to die. I knew that despite life’s many difficulties, I really did love being alive. The socks were done. I folded them neatly, knowing it was to be my last act on this earth. I had begun to weep when the alarm went off. I said, “What? What?” and my wife said, “It’s time to get up.” And so I did.

August 19, 2004 — It is obviously time to take a completely different approach, but I have no idea what the approach should be. Furthermore (quoth the raven), I often feel like pulling my life up by the roots anyway, and burning it like an old orchard or vineyard. What pleasure it would bring to stand before such a cleansing fire! Quite amusingly, I am being attacked by a giant crane fly at this very moment, and field-burning smoke is drifting in through the open window. Aack! Get away! There. Oh, great — now the neighbor is out spitting in his driveway again. I ask you, how can a humble writer revolutionize his life when he is always under attack, as I am? I have so much work to do — there are dozens of novels and stories I need to write, there are people to see and journeys to take — and it must all be done today. Instead, I am battling spitters and crane flies. Well, they’re real, anyway. They exist. I am telling the truth. No one can take that away from me. Not that anyone wants to. Besides, who needs the truth? We’re sick of the truth. What we need is some entertainment. Very well, then. Entertainment it is. When I woke up this morning, I was a giant beetle named Franz Kafka. When my mother came in to change the sheets, she was horrified. “Is this your antenna?” she said. I nodded meekly in her general direction, rattling my mandibles. “I thought so.” That’s all she said. She thought so. I can’t tell you how her bitter words stung me. My thorax quivered. My six repulsive, hairy legs squiggled aimlessly. She huffed out of the room. Just a few seconds later, I heard her voice addressing someone in the kitchen. “Be grateful your sons are normal,” she said. “Today, mine is a beetle. Tomorrow, who knows what he’ll be.” This was followed by a dull murmur. I knew right away that it was Mrs. Murphy and Mrs. Kratzenshade, my mother’s two best friends. I could even hear them nodding in agreement, because it always made their fake pearls rattle. Then Mrs. Kratzenshade said, “My Harold just received another promotion.” And Mrs. Murphy said, “That reminds me, I haven’t told you yet about my Dennis. He’s a lawyer, you know.” Mrs. Kratzenshade replied, “Yes, we know. Oh, how we know.” Then I heard my mother’s voice again. “My son thinks he’s a beetle.” At this I wanted to cry out, Thinks! Thinks! but I couldn’t, because beetles don’t cry out, they just sort of skitter and buzz, neither of which I had the hang of yet. “Maybe it won’t last,” Mrs. Kratzenshade offered in an insincerely sympathetic tone. My mother snapped, “You forget the time he was a fire hydrant for two weeks. Oh, I’m sorry,” she continued, “but you just can’t imagine!” And neither could I. But I didn’t need to. For a whole week, the dogs in the neighborhood wouldn’t leave me alone.

August 20, 2004 — In my Quarto are the complete texts of two novels: Ethan Frome, by Edith Wharton, and The Great Gatsby, by F. Scott Fitzgerald. I have read neither, so yesterday evening I started on The Great Gatsby. I read the first chapter, then my eyes gave out, so I put the book down and started wandering aimlessly around the house, doing my best to imitate the sound of a winter wind moaning under the eaves. This morning in the ten-minute time slot after breakfast and before it was time to head to the iris farm, I read the second chapter. So far, so good. There is a hint of melancholy I find appealing, but here and there the writing sounds almost as if the author had attended one of our ubiquitous modern writing workshops. This is just an early impression, of course, and might change. Either way, I am eager to see how and why The Great Gatsby occupies such a prominent place in twentieth century American literature, though it’s unlikely I will put the knowledge to good use. Who knows? Maybe someone will ask my opinion at a swanky cocktail party. Then again, they probably won’t, because I will make a point of arriving in our faded-red Toyota, and of being seen opening the door through the window with the outside handle. Who is he? (Sniff.) Isn’t it rather late for the gardener to be about? (Snort.) Who is he? Really, darling, don’t you know? (Smirk.) That’s F. Scott Fitzmichaelian, the famous writer. Quite eccentric, you know. And you should see him dance. (Sip. Chew.) Oh, really? (Gurgle. Smack.) He doesn’t look like a dancer. He looks more like a . . . more like a . . . oh, what is the word I’m looking for? Ahem! Yes. Well. We won’t worry about that. He’s charming, my dear, and that’s quite enough for me.

August 21, 2004 — So far, reading The Great Gatsby makes me glad of one thing: no one calls me “old sport.” Such is the power of great literature. I might add that our iris laborer read the book in his Advanced English class this past spring, and didn’t think much of it. “How was it?” I said. “Well,” he said, “heh-heh.” I said, “That bad, eh?” And he said, “I don’t know, Bill.” From past experience, I knew this was a horrible review. When he likes something, he says so. When he doesn’t, he calls me Bill. He loved Of Mice and Men and The Grapes of Wrath, and said they were great. The Sea Wolf? Very enjoyable. He likes Jack London. Saroyan’s The Human Comedy? He’s read it several times. He doesn’t read a book several times if he doesn’t like it. “What do you think of it so far?” he asked me yesterday when the subject of Gatsby came up. “It’s clever,” I said. “Frightfully clever.” He shoveled a handful of roasted peanuts into his mouth. The container was almost empty. “I’ll let you know,” I said. We ate scalloped potatoes and washed the dishes. This is what happens in real life. I try to tell the folks in Hollywood, but they just laugh. “Put some sex in there,” they say, “and you might have a winner.” I tell them, “You’re not listening.” They say, “Huh?” Next. Look. All I have is one minute. In one minute, I want you to tell me your story, and then I want you to describe your audience and convince me it will sell. Don’t give me any background. If you have to give me background, that means one of two things: either your story isn’t finished yet, or it’s too long. I don’t want paragraphs. I want faces. A story without faces won’t sell. People relate to faces. Okay? Ready? Go ahead. . . . Thanks. I, uh . . . That’s it. Time’s up. I told you, I only had one minute. Next.

August 22, 2004 — After two miserable weeks of ninety-degree weather, a fall storm has rolled in. It hasn’t rained much yet, but there have been a few nice showers, and a cool ocean breeze promises more to come. Once again, the air is a pleasure to breathe, and the daily battle to keep the house cool has been suspended. Yesterday evening we picked about fifteen pounds of fully ripe tomatoes. The rain would have cracked them if we had left them on the plants. The wind also blew in some new neighbors across the street and one house down, where no one has been living since the previous rough crowd disappeared quickly one weekend several weeks ago — though a few seemed to be hiding out inside for a short time after that — which is when the window on the side of the garage was broken by someone to whom they apparently owed money. Anyway, we’ll see what the future holds in that department. Hopefully the new “man of the house” won’t belong to the same spitters’ union as our other neighbor, Mr. Spit ’n Splat. Say, that would be a good name for a car wash. Anyway, I hope the landlord learned his lesson the last time around. Talk about a poor judge of character. After the troublemakers left, it took his dedicated hirelings three weeks to clean up the yard and house, and the people had only lived there a couple of months. Personally, I would have burned the house down and started over. In fact, I’d still like to burn down the other houses in the neighborhood, and dig out all the lawns and pull up the sidewalks. Then I’d burn our house and go live in the hills, and leave nature to reclaim its own. This area has suffered enough.

August 23, 2004 — So much for The Great Gatsby. My general feeling is that it’s a competently written short novel that is really nothing more than a long short story that could have been a shorter one. I hope I will be forgiven for saying the book is not great literature, or even particularly memorable, but if I’m not, I’m not, and I will do my best to carry on. Great literature is great because it transforms the outlook and understanding of its characters and its readers. Gatsby does neither. Fitzgerald’s people become upset when something distracts them from their superficial lives, but there is no reason to think they have undergone, or ever will undergo, a profound change in their thinking. Did I miss something? Probably so. To be sure, the author turned an elegant phrase. And he was obviously no dummy. But the fact remains, he didn’t push his characters far enough. He relied too heavily on his eloquence, and hoped his clever observations would carry the day. And they almost did. The wine, old sport, was served in beautiful glasses, but the taste was a bit disappointing.

August 24, 2004 — Two cups of strong black coffee and not a spark of life. I wonder — should I make a third cup? I don’t know. I never make a third cup. I don’t want a third cup. On the other hand, what about a cup of Armenian coffee? Yes, I think that’s what I’ll do. . . . Ah. There. I would have been back sooner, but I decided to wash the regular coffee pot first and get that out of the way. Now for my first sip. Oh, my goodness — that’s coffee. Wait. Let me take another sip. Lovely. This ought to get the old nerves jangling. . . . What a peculiar morning it has been. It’s ten o’clock. Half the day is shot. I should be making a ham sandwich, not more coffee. I should be on the phone with my agent, shouting in a fit of absolute brilliance, “I refuse to take a penny less!” But first I would have to find an agent, and sign his contract, and agree to pay his photocopying expenses. That could take months — years, even. So much for spontaneity. Then again, I could call an agent, tell his assistant that I refuse to take a penny less, and then quickly hang up. In fact, I could get a giant list of agents’ telephone numbers and do that all day and every day this week. Then, if I happen to do business with any of them later, they will already know I’m not a push-over. That makes sense. . . . The funny thing is, with all this talk about calling agents, the telephone just rang. I said, “Hello?” and an elderly lady said, “Vinnie?” So I said, “I think you have the wrong number.” And the lady said, “Who is this? Is this the Simpson residence?” I said, “No, it isn’t. And who are you? Are you a literary agent? Because if you are, I refuse to take a penny less.” Then I hung up. That took care of her. Imagine, a literary agent posing as an old woman looking for Vinnie. How stupid do these people think I am?

August 25, 2004 — It has been a long time since I’ve mentioned politics. I think that’s a good sign. I hate politics. Or, to put it more accurately, I hate politicians. I hate the lies they tell, and the steady stream of putrid garbage that flows through their corrupt beings and out of their twisted mouths. There is only one word to describe this year’s presidential campaign: vomit. And we still have to endure over two months of it. And will it end with the election? It doesn’t seem possible. And how many more lies will be told by then, and people killed, and how much money will have been made by the world’s low-grade Bush-like filth in Iraq and elsewhere? How many more economies will be hijacked, and cultures raped, and people made to go sick and hungry? And what do we get? “The Swift Boat Veterans for Truth,” a republican attack group with long-time ties to the Bush family which claims on TV that the democratic candidate for president lied about his military service in Vietnam. Imagine that, considering the president’s sterling record in that department. As I said, vomit. Pure vomit. The other morning, my wife and I saw a homeless man crossing the street in downtown Salem. He was worn out and old before his time. He was carrying his belongings, and his feet hurt. I say, let the politicians sit down on a park bench with this man and listen to his story. Let them take off his shoes and wash his aching feet. Your Swift Boat of Lies is sinking, my friends. Why don’t you do something worthwhile with your lives, instead of poisoning humanity?

August 26, 2004 — Several days ago, a writer-friend of mine suggested in one of his e-mails that I read “A Hunger Artist,” a short story by Franz Kafka. His exact words were, “If you got through ‘The Metamorphosis,’ then you must read ‘A Hunger Artist.’” “Metamorphosis,” of course, is Kafka’s much-anthologized story about Gregor Samsa, the young man who one day wakes up to discover he has turned into a large beetle — or maybe it is a cockroach, for I seem to remember a place well along in the story in which his mother cheerfully refers to him as a cockroach. Anyway. He was an insect, and it was all very tragic, and beautifully done, and not funny at all. And so, I was more than willing to read “A Hunger Artist.” But I promptly forgot all about it. Then, yesterday evening, I found a tiny slip of paper near my work table upon which I had written “A Hunger Artist.” Ah-ha, I said to myself, for at that moment I was alone in the house, A Hunger Artist. Realizing I had a few minutes to spare, I signed on to the World Wide Web and quickly found the story. I read the first translation I came to — probably a mistake, because I found another this morning that seemed a little better, though both had errors. Anyway, I didn’t read past the second paragraph this morning, so I can’t say much about the second translation. I can’t say much about the first, either, which makes me wonder why I brought up the subject of translations in the first place. Oh, well. I read “A Hunger Artist.” It is a very short story, and consists of a few long paragraphs. Once again, the story was different, as Kafka himself was different, in that his loneliness was an even greater burden for him than it is for most of us — or, rather, his loneliness figured far more prominently in his life than we are generally willing to admit it figures in ours. Kafka’s hunger artist is a man who fasts professionally, going without food for days and weeks on end in a public place. As such, he is just about the loneliest person on earth. One thing that makes him lonely is that no one is able to understand and appreciate the art of fasting. He doesn’t blame the spectators, because he knows they have never fasted and therefore cannot know what it’s like. Nevertheless, he finds their insensitive gawking ignorance almost unbearable. Eventually, when public fasting loses its popularity, the hunger artist is obliged to join a circus and fast in an area along the busy route to the caged animals. But circus-goers are eager to see the animals, not him. Still, he fasts. He fasts for so long that he is all but forgotten, and then he is finally found lying in his little heap of straw. With his last bit of strength, he whispers to the unfeeling circus manager that he could have eaten as much as anyone else, if only he had been able to find food to his liking. Then he dies, and the cage is used to house a panther everyone likes to see, and which seems utterly content to live in a cage. Again, it is all very sad, for it is clear that the food the hunger artist is referring to is food for his mind, or spirit. It certainly makes one think. What are we hungry for? And why are we so willing to live like the panther at the end of Kafka’s story?

August 27, 2004 — Since I’m between novels at the moment, I’m thinking it might not be a bad idea to reread “Metamorphosis.” I did sit down with that intention last night, but I quickly realized I was too tired to give the story the attention it deserves. I read a few poems instead, just for the pleasure of it and to relax, jumping at random from Sandburg to Eliot to Frost to Pound to Yeats to Auden to Cummings. This morning I remember almost nothing, except for Sandburg’s line about Abraham Lincoln being shoveled into the tombs and forgetting everything, in the dust, in the cool tombs. That’s quite an image: a great man being shoveled into his final resting place, while the entire nation looks on. And how do we know he was great? We need only look at pictures of his beautiful, amazing face, and notice the pain it mirrored and the transformations it underwent. Which of our recent presidents can be said to possess the tiniest fraction of Lincoln’s depth and character? And yet they have routinely traded on his name. If Lincoln were alive today and a political opponent of theirs, they would do their best to destroy him and his poor wife on television. And if they had been alive in Lincoln’s time, they would have attempted the same thing by whatever means at their disposal, because that is the only thing corrupt, empty, ignorant people know how to do.

August 28, 2004 — As it turns out, Franz Kafka will have to wait, because in yesterday’s mail I received a proof copy of a friend’s new short story collection, along with his flattering request that I look it over for typographical errors. There are nine stories in all, and the book runs about a hundred pages. I like his note: “Contact my agent for payment.” Yet nowhere is his agent’s name to be found. Hmm. Where are those glasses of mine? Oh, well. I guess I’ll have to do my proofreading without them. Joe went two town and eight a hamburger. Fine. I see nothing wrong with that sentence. I ought to have this done in no thyme. . . . Interesting. I just got off the phone with another friend, who says he will be stopping by later with a pile of magazines another friend passed along to him. The magazines he mentioned were Harper’s, The Atlantic, and Smithsonian, none of which I have seen in quite some time, mainly because I have no time. I hope The Atlantic has a piece by Nathaniel Hawthorne. Well, I guess it hasn’t been quite that long. But I do know it’s been a long time since I’ve found a short story in there that I’ve liked. I find most stories in The Atlantic to be well written from a technical standpoint, but safe, predictable, and boring. Either the writers don’t like to take chances, or the editors don’t, or both. Even more likely is that they don’t know how, and derive a feeling of security from painting by the numbers. Certainly, that’s an odd way for a writer or an editor to live, and terribly limiting, but it’s so common that no one in the mainstream even talks about it. As I’ve mentioned before several dozen times, they would rather attend workshops and talk about being “passionate” and “honing” their “craft.” This is about as logical as someone thinking he is expressing himself or herself by buying the exact same clothes everyone else is buying, and by imitating people on television. When one thinks of the great writers in history, it’s hard to imagine any of them attending workshops. They were too busy living and being outraged by narrow-minded thinking and ignorance.

August 29, 2004 — There is nothing like having a jolt of apricot vodka with a friend, especially after his son has tricked you into letting yourself be zapped with a fake cigarette lighter. But what was I to do? It was a nice-looking lighter, and he asked me to give it a try. So I did. The thing delivered quite a shock, accompanied by a buzz. I suppose the shock wasn’t really a shock, but a strong vibration. In any case, I jumped and yelled, and the lighter flew out of my hand, and then father and son laughed their fool heads off. After the joke wore off, we went inside and I poured us each a shot of vodka, which my brother brought on his last visit from Armenia. “You guys don’t deserve this,” I said, “but go ahead and drink it anyway.” Sitting at the table, we disposed of the shots in one gulp. I watched their expressions change as the 130-proof fluid coated their stomach lining. They were delighted. Before pouring another shot, I moistened some batz hatz, the flat, dry Armenian bread also known as cracker bread, or lavash, though in Armenia lavash is soft, not dry and crumbly. I brought it to the table and we ate some of the bread. Then we had another shot of vodka, and nibbled a little more bread. After that, my friend’s son, who knows enough about drinks to be a bartender, told me about one called an Irish Car Bomb. It’s a simple drink with only two ingredients: a pint glass about two-thirds full of Guinness Stout, into which is dropped a shot of Bailey’s Irish Cream, glass and all. Then you drink it. I said, “You leave the shot glass in there?” He said, “Yes.” I said, “But when you drink, doesn’t it hit your teeth?” He said it didn’t, but I told him I didn’t see how it couldn’t. By his bleary-eyed smile I knew I would never get a satisfactory answer, so I poured us all another shot of vodka. Judging by their tears of joy, it was the best thing I could have done. Later, after they had gone, I found a plastic bag full of magazines resting on the far end of the table. An hour or so later, my wife found them in the same place. “Oh, yeah,” I said. “Those are the magazines.” I picked them up and hauled them back to my lair, then separated the titles and arranged them by date so I could ignore them in their proper order. It’s important to be organized. If I weren’t organized, I’d never get anything done.

August 30, 2004 — Yesterday in New York, several hundred thousand people turned out to protest Bush and his evil actions on the eve of the republican convention. If the economy and employment situation are improving, as Bush says, and if the world is really safer because of the bloodbath in Iraq, as Bush says, and everything else were as Bush says, it seems unlikely that so many people would hate him and want him out of office. And if he is such a wonderful man, why doesn’t he have hundreds of thousands of supporters in the street shouting about how rotten his democratic opponent is? Why aren’t there hundreds of thousands of people out praising his war, and chanting “Bring ’em on”? Are they too busy counting their money? Or are they stuck in an unemployment line somewhere, wondering what hit them? Or maybe they are the parents of those whom Bush has sent to murder and be murdered in Iraq. Meanwhile, around and around he goes, wearing his blue work shirt with the sleeves rolled up, pretending to be a real working man. What an insult to people who really have to work, and whose work, though it saps them of strength and takes up all their time, often still isn’t enough to pay their bills. Clearly, he is laughing at them — which means he is laughing at millions. And so it’s no surprise that the streets of Manhattan were full of protesters, despite the heat, humidity, and possible danger. It’s no surprise that they marched with flag-draped cardboard caskets signifying Bush’s war dead. What is a surprise is that there is anyone left at all who cannot see through the man’s lies, and recognize what has taken place here and around the world during his time in office. I can understand the super-wealthy sticking by their boy, but anyone who has to work for a living, or anyone who cares about their children and grandchildren, or anyone with hope for a decent future who still thinks Bush and Company are on their side are living in a dream world or paralyzed by propaganda.

August 31, 2004 — Well, shucks. I finished my proofreading job. That means it’s time to read Kafka’s “Metamorphosis.” But now I don’t want to read Kafka’s “Metamorphosis.” I want to read something else. I’m not in the mood to read about a man who wakes up to discover he is a cockroach. Kafka was sick. And why does the room suddenly smell like chickens? The fan is running down the hall, that’s why. But I’m not worried. It won’t get far. The fan is on the window sill. I think it’s going to jump. What a ham. That’s it. Ham and eggs. No wonder I smell chickens. The fan ran all night, yet it still isn’t out of breath. But it has bad breath. Chicken breath. Feathers, dust, excrement, frightened chicken thoughts. Chickens should be allowed to run free. They shouldn’t be crammed into cages off the ground with the lights always on. Is there a chicken farm nearby? Not that I’m aware of. Then whence the smell? Whither the aroma? And what do chickens farm — that is, when they are given a choice? As I said, Kafka was sick, staying in his room all the time and writing about man-bugs and hunger artists. A guy like that won’t make it very far in this world, let me tell you. He won’t be elected to the city council or made president of Rotary. Yes, you have to feel sorry for someone like that. Very sorry indeed.

March 2003 April 2003 May 2003 June 2003 July 2003 August 2003 September 2003

October 2003 November 2003 December 2003 January 2004 February 2004 March 2004

April 2004 May 2004 June 2004 July 2004 August 2004 September 2004

October 2004 November 2004 December 2004 January 2005 February 2005 March 2005

Also by William Michaelian

POETRY

Winter Poems

ISBN: 978-0-9796599-0-4

52 pages. Paper.

——————————

Another Song I Know

ISBN: 978-0-9796599-1-1

80 pages. Paper.

——————————

Cosmopsis Books

San Francisco

Signed copies available

Main Page

Author’s Note

Background

Notebook

A Listening Thing

Among the Living

No Time to Cut My Hair

One Hand Clapping

Songs and Letters

Collected Poems

Early Short Stories

Armenian Translations

Cosmopsis Print Editions

Interviews

News and Reviews

Highly Recommended

Let’s Eat

Favorite Books & Authors

Useless Information

Conversation

E-mail & Parting Thoughts

Flippantly Answered Questions