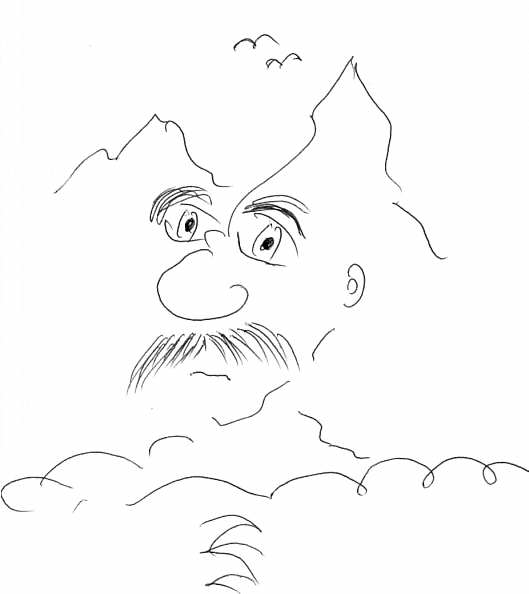

Look Homeward, Angel

by Thomas Wolfe

with an introduction by Maxwell E. Perkins, editor

Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York (1957)

Look Homeward, Angel is an inspiring, wonderful book, a book that is deeply moving and at times upsetting, so powerful and intense are its images. First published in 1929, it is American in the best sense: it is free-ranging, poetic, and full of the hungry, raw energy that springs from knowing there remains much yet to explore. It is constrained by nothing; Wolfe’s language is full, ripe, uninhibited. Moreover, his work is a refreshing and well-deserved slap in the face of much of today’s writing, which is often so weary, crippled, careful, tedious, humorless, and politically correct that it is unbearable to read.

Thomas Wolfe was born in Asheville, North Carolina, in 1900. He died in 1938, a victim of tuberculosis. But a reading of Look Homeward, Angel reveals a man already ancient in life’s wisdom. Angel is an autobiographical novel. In it Wolfe spared no one, especially his family, and least of all himself. His was a great mind imprisoned in a great, gangling body both of which in youth seemed always to be in the way. As the main character, Eugene Gant, he was often the brunt of laughter. From the beginning, Eugene lived a raging internal life. He wanted to know and see everything, and to be recognized as the loftiest, gentlest, and most powerful of heroes. He read constantly, forgot to eat, prowled about, and kept irregular hours. He tried hard, meanwhile, to fit in, and threw himself into typical boyhood pursuits. He delivered newspapers, and was given the part of town where it was hardest for the boys to collect, called Niggertown. He eagerly absorbed the rich culture there.

Eugene’s father, a carver of gravestones whose shop entrance was watched over by stone angels, was a strong, energetic man given to wild alcoholic binges. His mother was possessed by another kind of demon, that of acquisition. She was gifted in matters of money and real estate, and over the years managed to acquire a small fortune. But she refused to spend a cent. She bought a big house and took in boarders, who were often either sick or diseased in some way, or whose behavior was unsavory. Since they represented an income, her boarders were more important to her than her own children, with whom she was stingy to the point of cruelty, a part of herself she was unable or unwilling to see.

These characters, as well as Eugene’s brothers and sisters, are so well drawn that the reader might well drown in the family’s violent tug-of-war between reason and insanity, hatred and love, and bitterness toward, and desperately clinging faith in, each other. It is easy to see why Wolfe feared what his family’s reaction to the book might be, and how this kept him away from home for two years after the book’s publication. As it turned out, they were much more understanding than the townspeople, who were insulted and outraged. But Wolfe wasn’t unkind. He only wrote what he felt was true. He also recorded the good and happy things wherever and whenever he found them. His wit and laughter can be heard throughout the book.

Look Homeward, Angel contains some of the most passionate and poignant writing one is likely to encounter. It is poetic, rhythmic, colorful, and urgent. There are many unusual word combinations and descriptions that are highly effective. It is as if Wolfe was able to see things in far greater detail than their common names allowed, and recognized their acute interdependence. He wrote of Birth and Death as if they were dual personalities rooted deep within. He wrote of Eugene’s infancy as if from fully remembered personal knowledge. He revealed the relentless advance of physical erosion and decay in himself and in the bodies of the people around him, and showed the spirit lighting the way from within.

. . . Lying darkly in his crib, washed, powdered, and fed, he thought quietly of many things before he dropped off to sleep — the interminable sleep that obliterated time for him, and that gave him a sense of having missed forever a day of sparkling life. . . .

. . . He was in agony because he was poverty-stricken in symbols: his mind was caught in a net because he had no words to work with. He had not even names for the objects around him: he probably defined them for himself by some jargon, reinforced by some mangling of the speech that roared about him, to which he listened intently day after day, realizing that his first escape must come through language. He indicated as quickly as he could his ravenous hunger for pictures and print: sometimes they brought him great books profusely illustrated, and he bribed them desperately by cooing, shrieking with delight, making extravagant faces, and doing all the other things they understood in him. He wondered savagely how they would feel if they knew what he really thought: at other times he had to laugh at them and at their whole preposterous comedy of errors as they pranced around for his amusement, waggled their heads at him, tickled him roughly, making him squeal violently against his will. The situation was at once profoundly annoying and comic: as he sat in the middle of the floor and watched them enter, seeing the face of each transformed by a foolish leer, and hearing their voices become absurd and sentimental whenever they addressed him, speaking to him words which he did not yet understand, but which he saw they were mangling in the preposterous hope of rendering intelligible that which has been previously mutilated, he had to laugh at the fools, in spite of his vexation. . . .

In the simplest sense, Look Homeward, Angel is a coming-of-age story. A child is born; by painful increments, he finds out who he is and where he might be going. But Thomas Wolfe and Eugene Gant know there will always be areas of unexplored darkness. And so there is a restlessness here as great as that of Odysseus, the ancient, wide-eyed sailor who can only return home by embracing the adventure known as Life.

Back to Favorite Books & Authors

Also by William Michaelian

POETRY

Winter Poems

ISBN: 978-0-9796599-0-4

52 pages. Paper.

——————————

Another Song I Know

ISBN: 978-0-9796599-1-1

80 pages. Paper.

——————————

Cosmopsis Books

San Francisco

Signed copies available

Main Page

Author’s Note

Background

Notebook

A Listening Thing

Among the Living

No Time to Cut My Hair

One Hand Clapping

Songs and Letters

Collected Poems

Early Short Stories

Armenian Translations

Cosmopsis Print Editions

Interviews

News and Reviews

Highly Recommended

Let’s Eat

Favorite Books & Authors

Useless Information

Conversation

Flippantly Answered Questions

E-mail & Parting Thoughts

More Books, Poetry, Notes & Marginalia:

Recently Banned Literature

A few words about my favorite dictionary . . .

From Look Homeward, Angel

by Thomas Wolfe

. . . The only sound in the room now was the low rattling mutter of Ben’s breath. He no longer gasped; he no longer gave signs of consciousness or struggle. His eyes were almost closed; their gray flicker was dulled, coated with the sheen of insensibility and death. He lay quietly upon his back, very straight, without sign of pain, and with a curious upturned thrust of his sharp thin face. His mouth was firmly shut. Already, save for the feeble matter of his breath, he seemed to be dead — he seemed detached, no part of the ugly mechanism of that sound which came to remind them of the terrible chemistry of flesh, to mock at illusion, at all belief in the strange passage and continuance of life.

He was dead, save for the slow running down of the worn-out machine, save for that dreadful mutter within him of which he was no part. He was dead.

But in their enormous silence wonder grew. They remembered the strange flitting loneliness of his life, they thought of a thousand forgotten acts and moments — and always there was something that now seemed unearthly and strange: he walked through their lives like a shadow — they looked now upon his gray deserted shell with a thrill of awful recognition, as one who remembers a forgotten and enchanted word, or as men who look upon a corpse and see for the first time a departed god. . . .